2315 Aptitude.

Patreon

Subscribestar

Comic Vote

Reddit

Wiki

Holiday List

Twitter @betweenfailures

Contact me for a Discord invite.

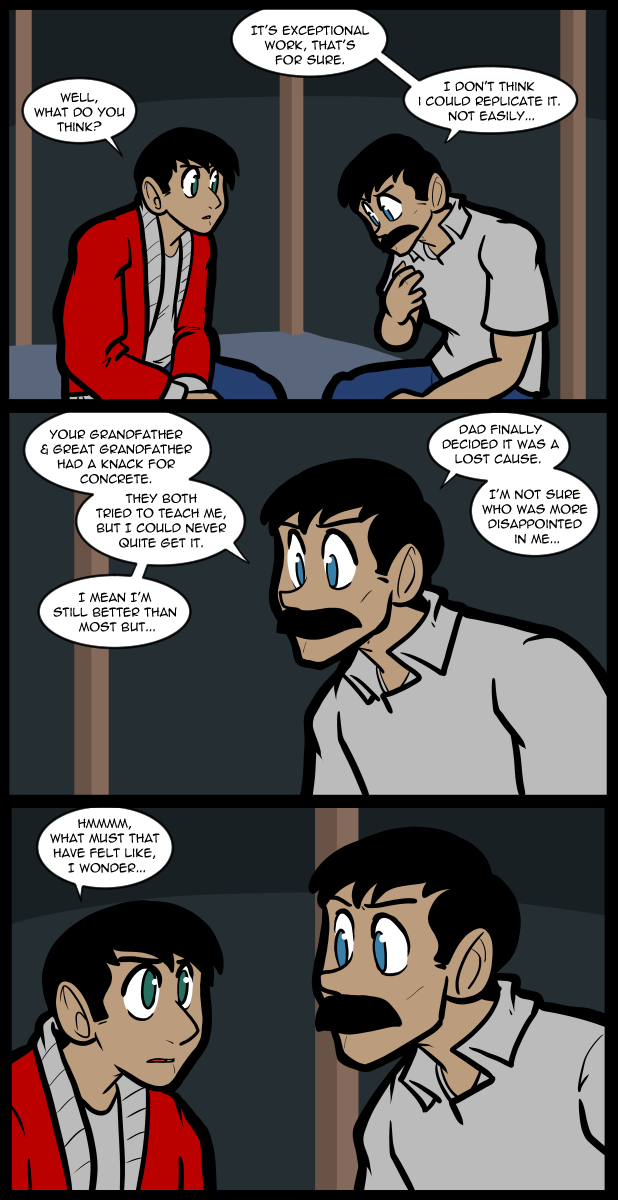

I think I spoke of this before when the subject of pouring concrete was brought up, but there are ancient techniques, lost to modern man, that are superior to the ones we use now. Of course generally technology improves over time, but there are occasions when some bit of vital knowledge goes missing & we regress. Concrete is something that mostly we don’t have to think about. You only notice it when something is wrong with it. Flaking, cracks, imperfections; those things make you notice it & how poorly it was set down. When it’s perfectly smooth or level, or whatever, it makes you not need to pay attention to it. Similarly people tend to not notice unobtrusive Patreon links on webpages, especially if they are too busy enjoying the lovingly crafted content. So calling attention to them helps a struggling creator monetize their efforts. It’s similar to driving on a nice stretch of road. When there are no potholes you don’t have to think about what you’re driving on.

It’s also easy to forget that every discipline has levels of excellence you can achieve. Even if you are a humble mason you can refine your craft the way Reggie’s forebears did. Though that excellence might go unnoticed & unappreciated it’s still worth striving for.

37 Comments

I believe the first science fiction book I ever read was _The Runaway Robot_ by Lester Del Rey. It’s narrated by the robot of the title, who is named “Rex”. At one point he talks about himself a bit, and it goes something like this:

We read my manual and found that one of my features is “a limited ability to imagine possibilities in order to better keep children safe while babysitting them.” We used to think I had curiosity, but no, I was only made with that limited ability. I wonder what it would be like to actually have real curiosity, what that might feel like.

When I was a kid this went right over my head, but as an adult re-reading the book I just love this.

By the way, I still dearly love that book. It’s nearly perfect. A boy has lived his whole life on Ganymede, a moon of Jupiter; his father moved there for work. Now the father is being rewarded with an even better job on Earth, so they are going to move. But it’s expensive to ship robots, and one robot is like another, right? So they plan to leave Rex behind and buy a brand-new robot on Earth. But the boy decides to run away, taking Rex with him, and they start trying to get to Earth on their own… together. I won’t spoil the ending but I’ll say it’s satisfying.

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/52666.The_Runaway_Robot

The main difference between the two is that Garret can at least admit that he wasn’t good at something, whereas Reggie is too proud to admit such a thing. This would probably be why Reggie in an earlier page said he was so unaccustomed to praise; because he’s unwilling to admit his mistakes and learn from them.

It’s also why Reggie doesn’t seem to have any actual competencies, apart from a working knowledge of building codes picked up from working in his fathers’ business. Of the two, the father is a much more likeable character.

It might be the other way, maybe Garret was more stingy with compliments than his dad, and as such Reggie got more defensive ’bout his skillsets

Ancient techniques, lost to man…. nah, not really. I’m an engineer and I’ve worked in London, one of the oldest cities in continuous occupation anywhere. I’ve visited places like Karnak and Luxor, and seen temples and castles in Japan. Roman concrete work is actually pretty rough, for the most part. They used a lot more cement than we do now, and it wasn’t good cement, but that’s why their structures stand the test of time.

We no longer produce the finely-fitted stonework some ancient civilisations used, but that’s only because of the time and cost. They lived in civilisations with large resources of cheap and slave labour and spent decades or generations on projects we would build in two or three years, we don’t. Look at the stonework in the Victorian reconstruction of London, for example. Most of that was produced by techniques the Romans or Pharoahs would have recognised, apart from steam engines. We couldn’t reproduce the timber work on Japanese temples or the Great Hall roof in Westminster, but that’s because we can’t get the wood any more. We can, and do produce single beams if we need to.

People marvel at the setting out of the pyramids, but any competent surveyor today could do the same. It’s done by astronomy, by eye, by lines of sight, by repetitive measurements and water levels. It’s not easy, but it’s not a mystery provided you understand the subject, which most people don’t. I used to have a field day exercise for my sons Boy Scouts, by which I showed them in a couple of hours how the Romans set out straight lines over long distances. The levelling of Roman aqueducts to maintain steady gradients over long distances is a remarkable feat of engineering, using the techniques of the time, but it isn’t mysterious.

There are types of concrete no one knows how to make anymore, blacksmithing skills no one knows anymore, woodcarving, leatherworking, papercraft, the list goes on and on. No one remembers how to do them because we stopped doing them in favor of other ways, & then nobody wrote them down. People all over are trying to rediscover stuff humans used to do, but don’t do anymore. It’s not really all that important how the most amazing katanas were made because people don’t generally go around hacking at each other with them. You can make an excellent sword with modern methods, but you can’t make it the way Masamune or Muramasa did because they never told anyone how they did it. The methods are undeniably lost. It doesn’t particularly matter, since something else filled the role, but the techniques are still lost.

Exactly. Even if someone invents a particular technique again (which happens a lot as it is, sometimes years later, sometimes months or days apart, but separated by geography), we may never _know_ that it’s the same technique. The knowledge of a given technique is lost, even if we later do it again but call it something different. Other times we may never rediscover it because we don’t use that technology anymore.

Welll… part of the “secret” of the Great katanas is known.. And it was the dutch whodunnit..

European iron of the time was *much* purer iron than the japanese could ever hope to make with the stuff they had available. So they bought great quantities of it at high price.

It got so bad that dutch ships’ officers had to prevent crewmen from stripping the nails from the ships and selling them on. All properly documented and logged in reports.

Between the “pure” european iron that carburised nicely and accurately, and the sulfur/carbide rich japanese iron, and the (perfected) folding technique they *still* used because they had to, and the differential tempering ( because they *had* to with japanese iron..) you get a hybrid weapon combining the best of two worlds, adapted to their particular style of combat/armour where swords actually still were effective as a weapon.

The only reason modern metallurgy connot recreate those weapons is in their method of manufacture. They’re “blended sheet” type, which is something that cannot be replicated in a homogeneous sheet of metal, however well alloyed.

A good smith can make blended sheet though. It’s “just” a variety of fire-welding after all.

There’s actually a fair number of blades made using the same techniques, same as with the “Ulfbehrt” swords, with the same “amazing” specifications as a result. They’re arguably better, even, given that the modern smith can basically pick and choose extremely precise alloys to start with, where the old masters had to tough it out with what they had on hand.

For the katana style blades, it’s more a matter of them not having been produced by a recognised japanese master-smith, and as such not being recognised as “katanas” by The Authorities ( aka. the japanese.)

And so Myths live on, overtaken by reality.

I think a distinction needs to be made between “we don’t know how to do it” and “we don’t know which of these possible techniques was used”.

For example discussions of the Battle of Hastings and the mythology of longbows vs armor break down into exactly what sort of arrows and armor are being tested, and that’s not easy. “This technique would be easy for them to do at the time if they knew about it, has a definite effect, but wouldn’t leave traces on artifacts unless we get really lucky” sorts of stuff.

When it comes to lost methods and craftmanship, I always think of Damascus Steel.

The USA sent men to the moon, but then lost the capability. We can’t do it currently.

According to an expert I trust, the plans for how to build the Saturn V rocket are not lost, but there is a whole lot of know-how that was never written down and was lost. How to machine the parts, what heat treatments were used, etc.

SpaceX is currently developing reusable rockets that will finally be better than the technology of the 60’s so we will soon be able to go to the moon again. But the proven old technology is lost.

This is another example of what you are talking about.

There are some. The methods of medieval stained glassmaking for lost for a couple hundred years until William Morris found them, for example. The thing I heard about “lost” Roman concrete recipes is that because they built with the idea of handling compression (the arch and dome) they didn’t need to add reinforcement the way we do today.

*were lost, that should read.

Romans didn’t need to use rebar, for particular designs (compression) that are less used today, but they did still make use of metal reinforcement.

rome.us/ask-us/why-the-colosseum-has-holes.html

As well, we can certainly build similar structures today, but there is no incentive or public will for that type of construction. We make use of rebar, plasticizers and advanced techniques because we can, and it allows us to get away with things that would never work in a compression only structure. Finally, a fanatical devotion to profit ensures that generally, even if one wants to focus on artistry vs everything else, limits get imposed restricting our ability to fully realize many peoples visions.

Plus, they set their concrete much drier and hand-packed it into place-very labor intensive, but-slaves. There are so many older technologies that should be revisited once materials science catches up, like the steam car. Remember, our nuclear powered ships and submarines are basically steamships. And electric cars were in common use as the internal combustion engine took over.

We could use Roman concrete techniques, any time we chose – but we don’t, because our techniques are far superior. We could build a pyramid, and align it at any star we see fit, but don’t see the need to do so. We could build longbows like those used at Crecy or Agincourt, but we don’t have the archers to make use of them – and we have machine guns.

No, this “lost technologies superior to ours” is just so much hokum, it sells books to people who don’t know any better. Thor Heyerdahl built a raft and sailed it across the Pacific, pretty much by applying modern knowledge in an ancient context. Tim Severin did the same thing with his reproduction galleys, reed and leather boats.

The “proven old technology” of the NASA Space Race, Gemini and Apollo era could be rediscovered. The designs survive, we have far better IT technology and metallurgy, plus ceramics and composites technology far ahead of the 1960s. The Russian designs still in use, aren’t significantly different in many ways. The Indians are re-using a lot of it.

You keep saying that people are arguing that old technology is superior, but we’re saying the methods are lost, not better. Or in some cases the infrastructure doesn’t exist. Maybe I missed one somewhere but you seem to be having an argument that no one else is.

Well, it’s pretty common for people to assume lost technology is better somehow. And a lot of people that talk about lost technology tend to push that angle. I seem to remember that being a big thing about why a lot of people are obsessed over damascus steel. Not to mention all the people who want to go back to some mythical past where things were supposedly better.

It becomes very easy to read that into someone that doesn’t actually mean it because the people who do believe so often don’t say it explicitly.

The Roman concrete depended on a particular chemical mix that ages by growing fibres that actually make it stronger as the years go by.

Modern concrete also gains strength as it ages.

Roman concrete was a different material from the Portland cement we use today: https://newscenter.lbl.gov/2013/06/04/roman-concrete/

https://www.ancient-origins.net/news-history-archaeology/researchers-discover-secret-recipe-roman-concrete-020141

https://www.extremetech.com/extreme/252092-roman-concrete-endured-thousands-years-seawater-pounding-cant

Another lost technology/material is Greek fire (seems napalm-like).

Can’t wait to see if Garret understands Reggie in the last panel, or had already understood him before this exchange.

That WILL be interesting, all right. We know Reggie’s overdramatizing things, but will Garret understand how much of the past he’s repeating?

Tangent: This reminds me of many things in the Anime PSA: Neglect For Success. It has too many nuggets to pick just one.

I married into a family whose great grandfather was a concrete guy. He built some of the sidewalks of Topeka way back when and his work remains today because it was solid.

I completely agree about how the art of it all has been lost over the ages. Today it’s about making the buck and moving to the next job as fast as you can. All of the things our civilization builds these days have baked in plans of how long should it last. If no one is going to want that car after X miles, don’t build a car to last beyond then. Contractors are always trying to find ways to get away with bare minimum to the code or worse, circumvent it all together. Sure, you’ve got the good folks out there, but far too many who aren’t.

The incentive works both ways. If I’m being paid to do something quick and cheap that’s going to be torn up in a year, making something that lasts a decade is a waste of effort and materials and instead you focus on making sure it does its job for that year. Building to the specs isn’t a lack of artistry, it’s doing the job requested.

Just to get this back on track, or somewhere near it, the author specifically says “I think I spoke of this before when the subject of pouring concrete was brought up, but there are ancient techniques, lost to modern man, that are superior to the ones we use now.”. But what Garrett appears to be saying is that certain named individuals’ technique was superior to his, which is a different matter entirely.

Anyone who thinks ancient workmen didn’t cut corners at times, is just wrong. Similarly the Roman technique of hand-packing a dryer concrete mix is really just a logical reaction to the constraints they were working under. It’s still done today, for certain specialist applications,

Roman-style concrete. We know what the ingredients are but we don’t know the exact amount in order to make the mixture work correctly. The Roman Pantheon for instance is a really good example of using concrete. The dome up-top isn’t stone. A mold was constructed and concrete was poured into it. When I was there I saw no signs of cracks, flaking, or even the odd chip. Another interesting thing about Roman concrete is that it can even settle and harden while submerged in water. Our concrete sucks.

Not true, roman concrete has been researched and their recipes replicated. And the underwater concrete thing is a myth, how it works is known and has been replicated, and improved upon, in modern mix designs. Modern concrete mix designs and placement techniques can do things roman engineers could only dream about. And for the record, I am a civil engineer and I know a fair bit about concrete. Properly mixed, placed and finished concrete can last forever, where things usually fail is too little cement in the mix, the wrong mix for the environmental conditions, or too much water when finishing.

Got a link to this tid-bit? I’d be interested in reading up on it.

Not really, no, it is what I learned in my concrete courses when I took Civil Engineering 35ish years ago.

Jackie, this has got to be your best Patreon segue yet, well done.

hahahahaha cannot…resist….subtle messaging….signed up!

Mwahahahaha!

While I would not classify Reggie as a great guy, I don’t think he is being overdramatic here. I feel like it hurt quite a bit when his father gave up on him (and yes, that’s what I feel happened) and now that Reggie has his attention, it is hard to move past that. The comic is called “Between Failures” for a reason, and the failure Reggie feels most sharply is this one.

The previous discussion on cement pouring was on comic #2099